In Long Life Learning: Preparing for Jobs That Don’t Even Exist Yet, Michele Weiss explores key questions about the nature of careers, skills, higher education, and work lives during an era when the probability of living 100 years is greater than at any time in human history.

Facilitating the ongoing, voluntary, and self-motivated pursuit of knowledge that helps people to through lifelong learning is part of librarians’ career DNA. Lifelong learning is core to the mission of academic and public libraries of any shape or size. This makes libraries a natural home for long-life learning as well.

What is Long Life Learning?

As work lives lengthen due to increasing lifespans, Weise describes “long life learning” as a cycle in which adults engage in alternating periods of learning and work multiple times over their working lives. Drawing on the “open loop” learning concept developed by the Stanford Design School’s Stanford 2025 project, these periods may entail educational deep dives into a topic, followed by applied learning through practice and teaching, on repeat. A career may include periods of study and practice-based learning, with the smooth transfer of skills from one field to another. Instead of a straight line of career growth, imagine loops or branches across a lifetime including jobs that don’t yet exist.

Weise provides an overview of the current inequitable education infrastructure in North America, examples of new alternative models for long-life skill development and the “human+” skills needed for adaptation. Weise analyzes the roles that employers, higher education and individuals can play within the new long-life learning paradigm as well.

Lifelong or Long-life learning?

The alternating periods of learning and work/practice envisioned within the long-life learning concept give a more concrete shape to the core purpose of lifelong learning. While many individuals and organizations aspire to the lifelong development of knowledge as an ideal, it’s hard to remain engaged, stay motivated, or sustain learning indefinitely and forever. The alternating periods of learning and doing provide a pathway toward the same goal while introducing more types of educational experiences and mobility across industries. Inequities in the current educational system further complicate career sustainability and advancement, as Weise details. Weise presents long-life learning as an alternative poised to deliver more equitable access to education. This approach also offers new possibilities for economic mobility and benefits to employers, the economy, and society.

Weiss contrasts these loops of long-life learning with the current realities and inequities of a higher education system that primarily serves young adults by front-loading four+ years of education before starting a career. The current models inadequately serve potential learners who are already working, over 25 years old, and those from underserved communities. The barriers to librarianship such as degree requirements are well documented including “Changing the Racial Demographics of Librarians” by Curtis Kendrick, published by Ithaka S+R. Long-life learning aligns well with the findings of Kendrick’s report.

The “long” part of long-life learning purposefully takes advantage of the communication, interpersonal, and leadership skills that compound through decades of practice working with others that can be translated across industries or roles.

“Human and Human+” Skills in the Library

As the library community identifies the role of artificial intelligence for our communities and within our work we can begin with the role of human skills in our industry. Weiss describes human skills as “Capabilities that robots or machine learning cannot simulate.” You may have heard human skills described as soft skills or interpersonal skills, including emotional intelligence, adaptability, communication, and conflict resolution. Libraries frequently include variations of human skills in position descriptions, and this trend is likely to continue. When industry knowledge and human skills (e.g., systems thinking and teamwork) are combined with technical skills to work with data these become a hybrid of “Human+” skills.

Libraries serve as fertile ground for developing “Human+” skills and applying the long-life learning model. These human skills are essential to delivering service, collections, and experience to diverse communities. Libraries can continue to be a hub for developing “Human+” skills in the local community. This builds on their existing role in guiding people toward career training and civic learning.

Weise helpfully notes “…just because we’re human doesn’t necessarily mean we’re great at the human side of work. In fact, human skills require practice; they are not innate.” These skills identify staff in your library who are interested in learning about artificial intelligence, machine learning, data wrangling, or programming.

Start long-life learning at your library

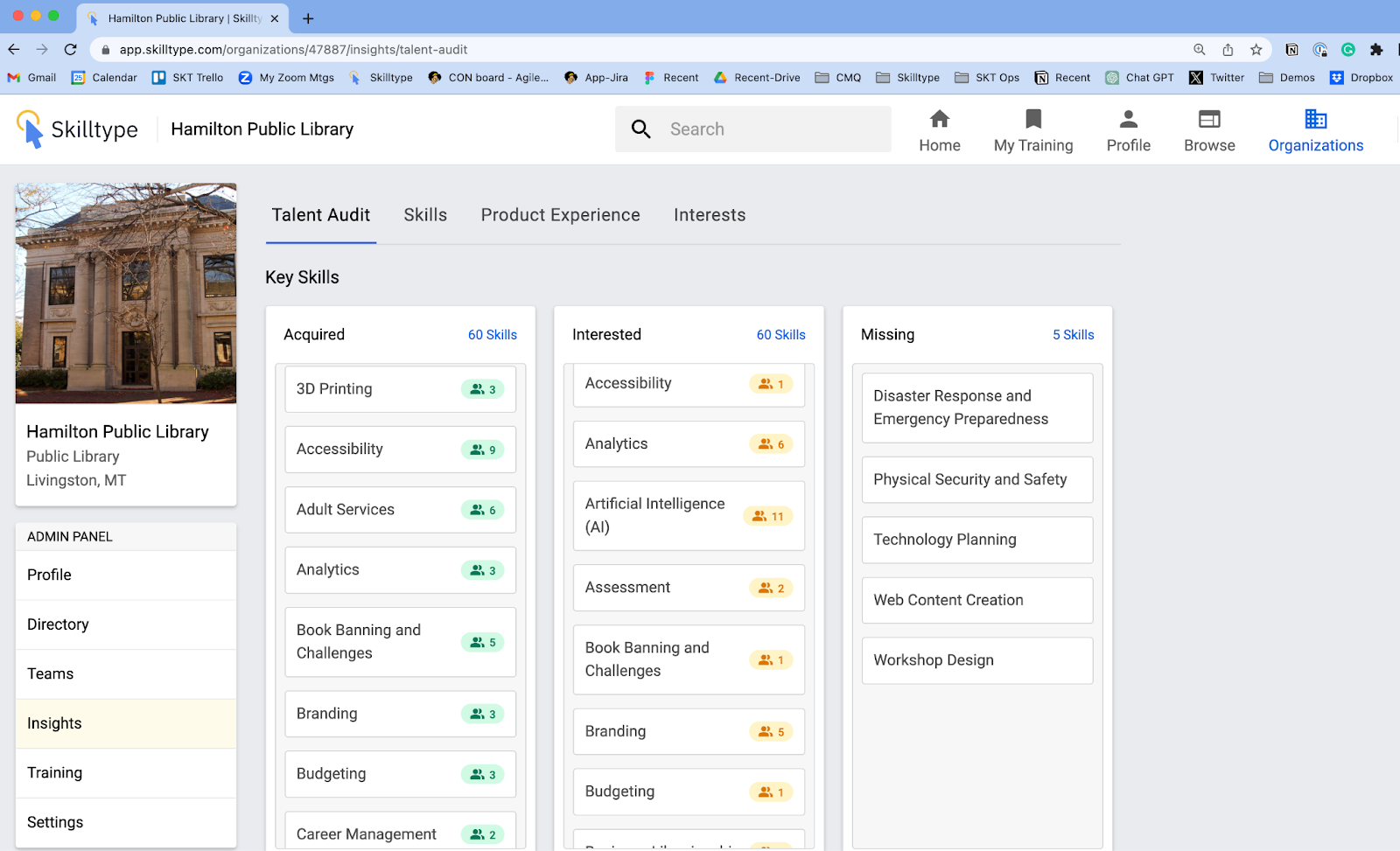

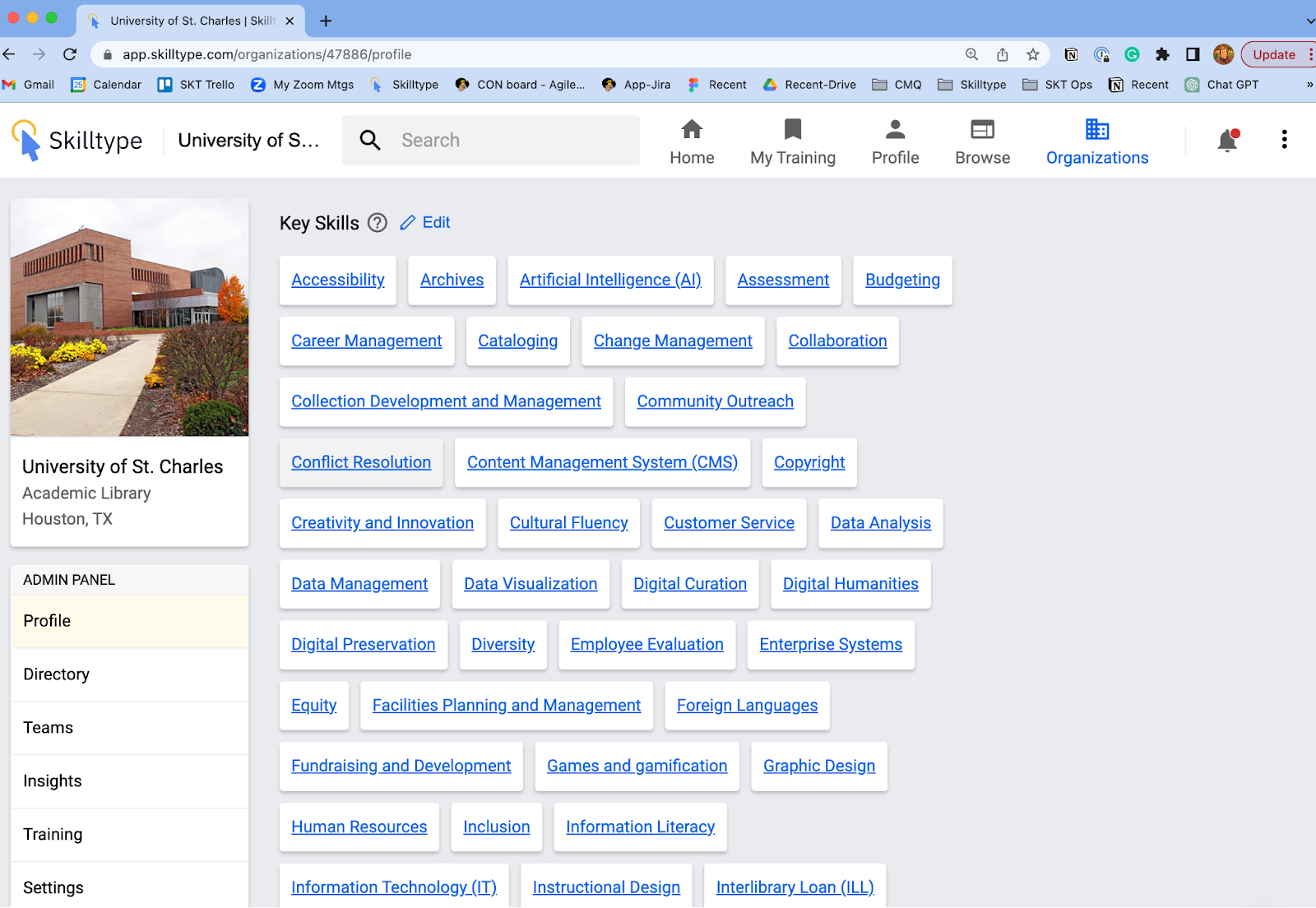

To get started forecasting the skills and roles that a library may need in the future, take a skills inventory. This will help better understand the current state of skills and compare them to current or future community needs. Skilltype can help with standardized competency data for the information professions and on-demand training resources.

Contact Skilltype for a demonstration to help your organization understand current skills and identify staff member interests. This will help you anticipate the roles needed in your library’s future.

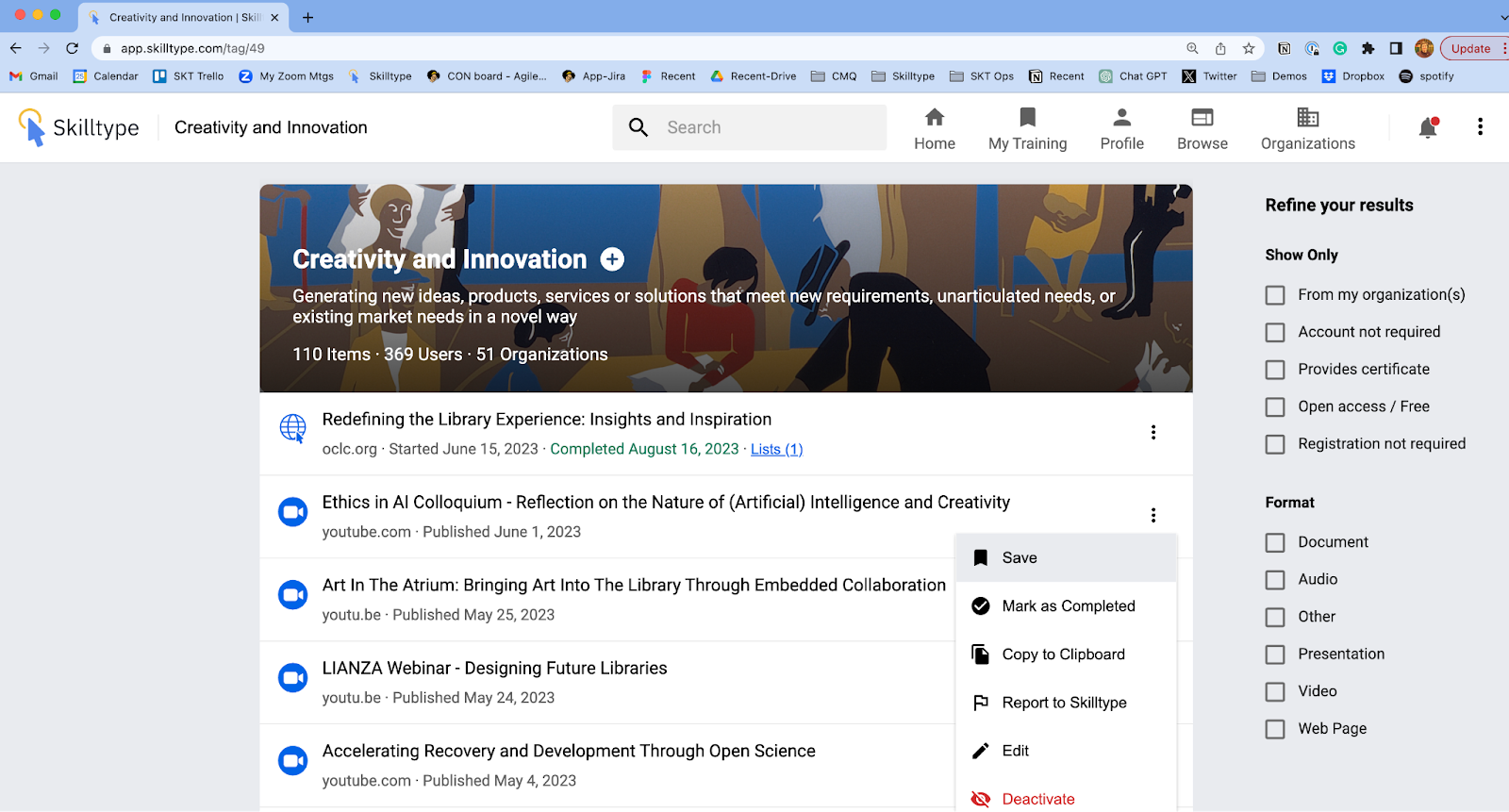

Libraries can invest in upskilling and reskilling employees by making on-demand training available to learn within the flow of work. Skilltype’s index of training resources makes it possible for staff to independently explore emerging information and technical or human skills. Skilltype provides automated weekly personalized training recommendations as a continuous invitation to grow. Managers are also able to curate training lists to advance learning focused on team or individual goals.

Human+ skills to help managers cultivate skills in others, conflict resolution, negotiation, and relationship building can be a good start. Equip staff with the tools to identify their interests and curate their careers. Providing resources to cultivate adaptability and the ability to communicate across domains will help prepare staff for the future. Your library can identify staff interested in learning about artificial intelligence, machine learning, data wrangling, or programming. Encouraging these staff by identifying projects to practice new information and technical skills. Also, Evaluate your library’s professional development policies. This balances resources for upskilling, reskilling, and practice-based learning to meet the needs of today and the future.

To learn more, Skilltype recommends:

- Read Long Life Learning by Michelle Weise

- Watch one of Weise’s interviews such a this interview with the University Innovation Alliance.

- Dive deeper into “human+” skills by viewing R. David Lankes’ recent presentation at the Enssib event 1, 2, 3… IA ! Intelligence Artificielle, Métiers et Compétences where Lankes describes the combination of librarians and artificial intelligence as “Augmented Intelligence.”

- Join us for an upcoming Skilltype Town Hall to meet library leaders focused on the future of library roles and skills

- Contact Success@skilltype.com to schedule a consultation to explore your organization’s talent data